…but what’s FontEdit?

It’s an app which allows you to generate and use custom fonts in embedded systems’ displays. See here for an introduction.

Release notes

The version released today brings the following improvements:

- exported source code is wrapped at around 80 columns,

- the source code contains a pseudocode explanation of how to retrieve individual font glyphs,

- more user-friendly Undo/Redo functionality.

New features:

- exporting ASCII table subset (skipping the characters that you don’t need) - helps to reduce font size when you only use a bunch of characters and not the whole ASCII table,

- checking for app updates at start-up.

The binaries for Windows, MacOS and Ubuntu/Debian/Raspbian are available from FontEdit’s GitHub Releases page.

The rationale behind exporting font subsets

A font source code, as understood by FontEdit (and embedded systems displays) represents a collection of bitmaps of the font’s characters (where, by definition of bitmap, each pixel is stored as 1 bit). Therefore to load all printable characters from the ASCII table, which is between code 32 and 126 inclusive, it takes 95 small bitmaps, each representing a single character.

Take a very small font as an example – 8x8px:

It takes 8 bytes to store a single 8x8px font character (glyph): 1 byte (8 bits) to store each row, times 8 rows. Times 95 glyphs, it’s 760 bytes to store the whole font.

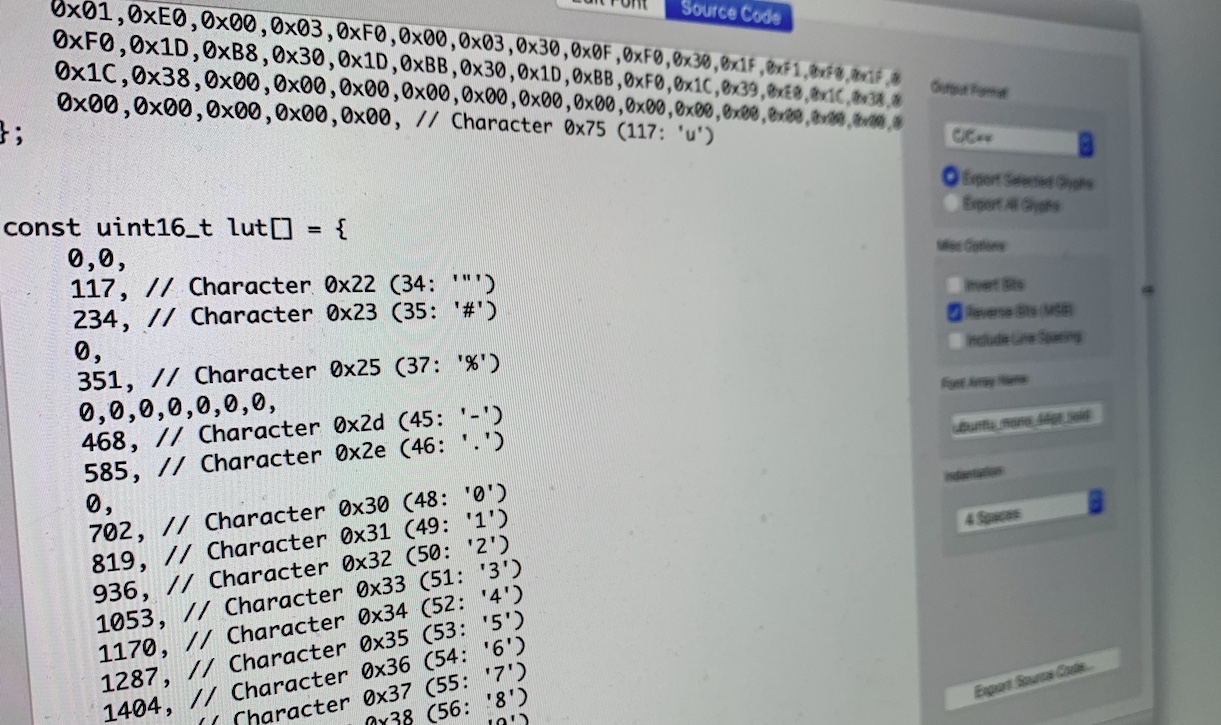

Now let’s take a larger font, something what FontEdit was designed for. Ubuntu Mono 44pt:

This 44pt font is actually 22x39px. Each row now needs 3 bytes (22 bits + 2 unused bits), times 39 rows. 3 x 39 x 95 glyphs –> 11115 bytes or almost 11KB. And it will eventually need to be loaded into RAM 😱. You can’t always afford this kind of memory expense. But many times you don’t need the whole ASCII table worth of characters.

Say you work on an OLED alarm clock, and you want to display the current time with a huge font.

You’d possibly only need these 14 characters: 0123456789:APM (or 11 characters for a 24-hour

clock). It only takes approx. 7 to 10 times less memory than the whole printable ASCII table.

Preserving character ASCII codes in a subset export

The regular (full) font source code export comprises an array of bytes representing a font,

character by character, starting from ' ' (ASCII 32) and ending with '~' (ASCII 126).

It’s designed to easily match individual font characters with their respective ASCII codes

– retrieving specific character data can be expressed with the following pseudocode:

// font - the font data array

// bytes_per_character - the number of bytes that holds a single character

offset = (ascii_code(character) - ascii_code(' ')) * bytes_per_character

char_data = font[offset] // char_data points at character's first byte

For a subset export, where only specific characters are in the output, the

ASCII code <–> array index relationship for the font array is lost. Back to our example,

a font array containing '0123456789:APM' would yield the bytes for 0 when you ask for

a space (ASCII 32), 1 when you want to print an exclamation mark (ASCII 33), and so on.

When you try to print 0 (ASCII 48), the code would request an index that’s out of

bounds – because there are only 14 characters in the font array.

To preserve the ASCII code to font array index relationship, a helper look-up table is defined alongside the font array. The look-up table values are font array offsets for respective characters, relative to these characters’ ASCII codes. Sounds complicated, but here’s an example:

// Using 8x8px font to make the example simpler

const unsigned char font[] = {

0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00, // Dummy blank character

0x60,0x50,0x90,0xA8,0xD0,0x50,0x20,0x00, // Character 0x30 (48: '0')

0x20,0x60,0x20,0x20,0x20,0x20,0x00,0x00, // Character 0x31 (49: '1')

0x70,0x10,0x10,0x20,0x40,0x40,0x00,0x00, // Character 0x32 (50: '2')

0x60,0x10,0x30,0x30,0x10,0x10,0x60,0x00, // Character 0x33 (51: '3')

0x00,0x30,0x50,0x10,0xF0,0x10,0x00,0x00, // Character 0x34 (52: '4')

0x70,0x40,0x40,0x30,0x10,0x10,0x60,0x00, // Character 0x35 (53: '5')

0x30,0x40,0x00,0xD0,0x48,0x50,0x20,0x00, // Character 0x36 (54: '6')

0x70,0x10,0x10,0x20,0x00,0x40,0x00,0x00, // Character 0x37 (55: '7')

0x30,0x50,0x70,0x70,0x50,0x50,0x20,0x00, // Character 0x38 (56: '8')

0x60,0x10,0x90,0x70,0x10,0x10,0x60,0x00, // Character 0x39 (57: '9')

0x00,0x00,0x20,0x00,0x00,0x20,0x20,0x00, // Character 0x3a (58: ':')

0x20,0x20,0x70,0x50,0x70,0x90,0x00,0x00, // Character 0x41 (65: 'A')

0x80,0x98,0xD8,0xF8,0xA8,0x88,0x00,0x00, // Character 0x4d (77: 'M')

0x60,0x50,0x50,0x70,0x40,0x40,0x00,0x00, // Character 0x50 (80: 'P')

};

//

// Pseudocode for retrieving data for a specific character:

// offset = ascii_code(character) - ascii_code(' ')

// char_data = font[lut[offset]]

//

// Characters that are not exported use 0 as font array index,

// falling back to a dummy blank character

//

const unsigned char lut[] = {

//32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39

0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,

//40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47

0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,

0x08, // Character 0x30 (48: '0')

0x10, // Character 0x31 (49: '1')

0x18, // Character 0x32 (50: '2')

0x20, // Character 0x33 (51: '3')

0x28, // Character 0x34 (52: '4')

0x30, // Character 0x35 (53: '5')

0x38, // Character 0x36 (54: '6')

0x40, // Character 0x37 (55: '7')

0x48, // Character 0x38 (56: '8')

0x50, // Character 0x39 (57: '9')

0x58, // Character 0x3a (58: ':')

0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,

0x60, // Character 0x41 (65: 'A')

0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,

0x68, // Character 0x4d (77: 'M')

0x00,0x00,

0x70, // Character 0x50 (80: 'P')

};

As you can see, using a LUT makes it even simpler to retrieve a specific character from the

font array. And it obviously reduces the memory overhead heavily. Be aware that the above code

will result in an out-of-bounds array access for characters above 'P' in the ASCII table.

At the end of the day, if you export a subset, it’s assumed that you know what you’re doing :).

Your text drawing code would probably need to be changed a little bit to support font subsets, but the changes are straightforward, and likely worth the effort.

Thanks for reading through!